the night watch: dealing with bats Surrounded by intrigue, myth, fear and fancy, the bat is truly a remarkable creation. How many an idle youth has tossed a pebble into its erratic, drunken flight path and watched in amusement as it honed in its radar to check on what it fancied was a plump moth or other tasty morsel of the entomological world? Bats are not blind. In fact all bats have eyes and some have excellent vision. Yet they rely on their echolocation abilities to navigate and catch their prey in the darkness. Emitting high frequency sound pulses that bounce off objects, they can track even the tiniest insects. Contrary to popular myth, bats do not suck blood either. Only three of the approximately 950 species of bats even live on blood, and they are found in Central and South America. These “vampire” bats may bite a toe or an ear (not the neck) of an unsuspecting victim and lick up the blood. In our locale, the Large and the Small Brown Bat are the most common. These bats are gregarious, living in maternal colonies. They are also very territorial and not easily inclined to abandon their roost. And that’s okay — unless that roost happens to be in your overhang, behind your chimney, or in your attic. Friend or Foe In many parts of the world bats are essential to the ecosystem. They consume pests that damage crops and foliage. They spread seeds and pollinate plants. Bat droppings are an excellent fertilizer and provide nutrients for other life, particularly in cave systems. In one night, a bat can consume one and a quarter times its body weight worth of mosquitoes or other marauders of our peaceful hammock retreats and backyard cookouts. In light of concerns about West Nile and other mosquito-borne viruses, bats ought to be considered our close ally indeed. But Eric Ammerman, Senior Public Health Sanitarian at the Monroe County Health Department cautions against expecting bats to eliminate our mosquito problems. Sure bats will eat mosquitoes, he explains, but they are more likely to go after larger, juicier fare, like moths. Besides being over-rated as bug-zappers, there is also the concern for rabies. At the health department, the “bat- phone” has been ringing off the hook. From late July to the first week in September, bat season is in full swing, says Ammerman. It’s not that the bats aren’t around at other times, but during this period the younger bats are just getting out and learning how to fly. Ammerman likens it to teenagers learning to drive, they sometimes make mistakes. These young bats may not find the proper spot in or out of their roost and inadvertently end up in the house through an open window or some other neglected hole or crevice. So finding a bat in your house at this time of the year is not uncommon. As long as there is no contact with the bat, all is well. Anyone coming in contact with a bat testing positive for rabies must receive post exposure treatment, since rabies, once contracted, is in all cases fatal. The treatment consists of a series of relatively painless shots spread over a period of one month. Only a very small percentage of bats tested are rabid, but if there is any contact, even secondary contact such as with a pet who has touched a bat, call the health department, says Ammerman. The health department should also be called if you are unsure if there has been contact, such as when an infant was in the room, or a sleeping child or adult, or an intoxicated or mentally disabled person. Even if there is a remote concern of having been exposed to a rabid bat the shots are considered necessary. Most importantly, if there has been any contact, or if the bat was in a room with a sleeping person, don’t release the bat, says Ammerman. “If the bat is let go, the state recommends rabies treatment. And that’s a lot of people getting treatment unnecessarily. With a family of four, you may have eight to ten thousand dollars in medical costs that are probably unnecessary. We would have sent the bat in for testing and 98 percent of the time it’s going to come back negative and that’s the end of it,” he says. If a bat is found and it is absolutely clear that no one came into contact with it, the bat does not need to be tested. Another concern with bats is the build up of bat feces, called guano. Histoplasmosis is a fungus disease that can, in some cases, be contracted by inhaling air-borne spores contained in the dust of bat manure. Ammerman recommends caution when cleaning up or disturbing bat guano. A protective mask should be worn if handling it and the area should be misted with water before it is disturbed to reduce the chance of producing air borne particles. The real Batman Brent Snyder, of Bat’L’Ax in Attica, NY, thinks bats are fine. And he ought to know since he keeps a couple hundred of them in an abandoned garage on his property. But they don’t belong in a house, he says. They’re filthy, carry diseases and can have mites and fleas. Snyder began removing bats from peoples homes as a way to help pay the bills after reconstructive back surgery forced him out of his job in heavy steel construction. But soon it became his business. Dealing with wild animals is nothing new to Snyder. “I’ve done nuisance wildlife work ever since I can remember. I was seven years old and catching coons for people out of their homes and garages,” he says. The cost of having bats removed from your home usually starts out around a thousand dollars, says Snyder, depending on how much work is involved in sealing up other potential bat roosts. Catching the bats is the easy part. Ninety percent of his work is sealing up the holes. The work sometimes involves extensive repairs like new windows and roof work, as well as a lot of caulking and filling, Snyder says. Removing the built up bat guano, on the other hand, is much more costly. The typical guano removal job starts out around four thousand dollars. Guano removal usually means taking out all the attic insulation and replacing it. The material is treated as bio-hazardous waste and its removal requires a full hazardous material suit and respirator similar to that used in asbestos removal. Once, when Snyder was inspecting a home for bats, he lifted up the attic hatch and a pile of bat manure dropped near his face. He had only a face mask on and some of the dust leaked around the mask and he contracted histoplasmosis. It was a long treatment and recovery process and Snyder says he still has lingering effects from the ordeal. He’s more careful these days. “Now, whenever we go in, even just to inspect a place, we completely suit up, “ he says. Snyder doesn’t seem to mind the close proximity with bats and he’s not easily deterred. He says he has been bitten many times over the years. “Sometimes when I’m in attics and they are flying around they land on me. The first instinct is to grab them and that’s when they get you,” he says. Snyder keeps his rabies shots up to date, a necessary precaution in the wildlife control business. He gets tested for his rabies titers, or measure of rabies antibodies, yearly. “My titer’s are high. If a bat bit me, it would probably get rabies,” he jests. Snyder has done some jobs where he has removed more than a thousand bats in one house. He catches the bats in trap boxes and they are released at DEC approved sites across the state. Snyder keeps close tabs on the bats that he raises on his property. Observing these bats helps him know when to get to work. When the bats start flying about he knows he can begin his bat removal season. When they go into hibernation he knows it’s time to shut down for the year. On occasion he gets a job in the winter when there is a cold snap and a hibernating bat tries to move to a warmer area inside the house. Almost all bats leave the house for the winter and hibernate in caves. But if it finds a warm enough spot, a Large Brown Bat may winter in a home. Do-it-yourself bat-proofing: To eliminate the bats, the first order of business is to find the roost. Look for piles of guano (dry, black, droppings slightly larger than those left by mice) or dirty brown discolored areas around holes or cracks. Listen for their high pitched, chirping squeaks. Do a “bat watch” at dusk to observe where they leave the building. The next step is to eliminate other possible roosting areas in the home because the bats will try to return after being evicted. Any crack or hole larger than _” should be closed up using caulking, heavy screening , expanding polyurethane foam, or by making the necessary repairs to the problem areas. Once the alternative roosts are sealed you can address the active roosting area. Wait until the bats leave at night and close up the entry point. This should never be done during late May to early July because young bats that cannot yet fly could become trapped inside and may find a way into the house or die and create an odor. A good time for bat-proofing is in the early spring before the bats return from their winter roost, or late in the fall after they have left. If you’re more comfortable working in the daylight, another option is to install a one-way exit over the hole. Install heavy screening over the hole and fasten it only at the top and sides, leaving the bottom open. When the bats leave the roost they drop down through the bottom opening to begin flying. When the bats return at dawn, they head directly for the hole, drawn by the smell, and will run into the screening and be unable to enter. Once you are sure the bats have abandoned the roost, the hole can be permanently sealed up. For more information: What to do if there has been contact with a bat

What to do if a bat gets inside your house

Note: If anyone has, or may have had contact with the bat, do not release it. Capture the bat and take it to the health department for testing. |

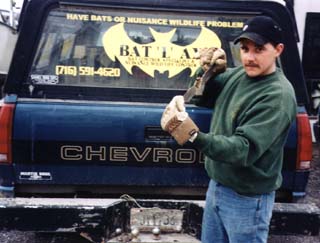

The real Batman in gear. Brent Snyder uses special equipment and clothes when he cleans-up bat guano. Submitted photo.

The real Batman in gear. Brent Snyder uses special equipment and clothes when he cleans-up bat guano. Submitted photo.