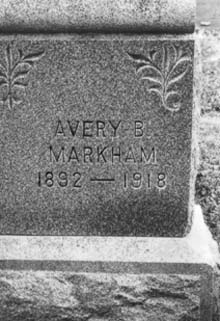

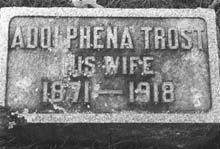

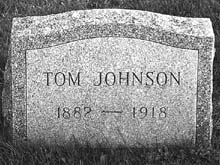

Chances are every local family has a member, or two, who was sick or died in the great influenza pandemic that swept around the globe and across America in 1918-19. More deaths are attributed to the great pandemic than any other disease, more people died of influenza in a single year than the four year Black Death Bubonic Plague of the 14th Century, or of the “Great War” (WWI) that raged at the same time. Estimates of the number of deaths range widely, 20 to 100 million. Most historians believe 40-60 million most likely. By comparison, there were 9.2-million combat deaths in WWI. The disease inexplicably struck healthy young adults in their 20s and 30s first before striking older people and children. Symptoms began with a dull headache and burning eyes leading within a few hours to chills, fever and body aches and shivering. Strange mahogany-colored spots then would appear on the cheekbones, spread to the ears and eventually cover the face. Delirium set in along with breathing difficulties, leaving victims gasping for breath with contorted purple faces with bloody saliva frothing from the mouth. It was unlike any disease previously encountered in the United States, or anywhere else in the world, so unlike previous flu-like illnesses that at first doctors and public health officials were unsure what the bizarre affliction was. in·flu·en·za [Italian, from Medieval Latin] used to refer to illness that comes from the cold, “influenza del freddo.” Earlier known flu-like illnesses, also called grippe, had never appeared like this, were never this deadly. Typically annual influenza outbreak kills only one-tenth of one percent of the population. In 1918-19, five percent died—within days, sometimes hours. Doctors simply didn’t know how to treat this strangely virulent and deadly disease. They didn’t even know what to call it. The first reports of the epidemic came from Spain where wild reports spread giving it the misleading name “Spanish Flu.” Today we know, like all viral influenza, the origin of the 1918 strain was Asian. Rapid spread Ultimately 25 percent of all Americans fell ill with the 1918 flu, including 40 percent of sailors in the US Navy and 36 percent of soldiers. In 1918 the world was still two decades away from the introduction of the electron microscope with which the virus was first discovered. The medical community was baffled. Some claimed the cause was bacterium because when death came the cause was fluid filled lungs not unlike bacterial pneumonia with which they were familiar. Some called it brocheopneumonia, or simply epidemic respiratory infection. Physicians had no medicines for it. There were no known treatments, there was no way, in 1918, to get oxygen into fluid-filled lungs. Frustrated doctors had no way to relieve suffering and the horrific misery of victims’ suffocating death. One of most poignant influenza stories we have describing what it was like to suffer from the disease comes from Thomas Wolfe, who wrote a thinly veiled account of his older brother’s death in his novel, Look Homeward, Angel. Wolfe was a student at the University of North Carolina when he was called home because his 26-year old brother Benjamin was ill with the flu. “Ben’s long thin body lay three-quarters covered by the bedding; its gaunt outline was bitterly twisted below the covers, in an attitude of struggle and torture. It seemed not to belong to him, it was somehow distorted and detached as if it belonged to a beheaded criminal. And the sallow yellow of his face had turned gray, out of this granite tint of death, lit by two red flags of fever, the still-black three-day beard was growing. ... Ben’s thin lips were lifted, in a constant grimace of torture and strangulation, above his white somehow dead-looking teeth, as inch by inch he gasped, a thread of air into his lungs. The next day, “By four o’clock it was apparent that death was near. ... Ben had brief periods of consciousness, unconsciousness, and delirium -- but most of the time he was delirious. His breathing was easier, he hummed snatches of popular songs, some old and forgotten, called up now from the lost and secret attic of his childhood. Gradually Ben sank into unconsciousness. “His eyes were almost closed; their gray flicker was dulled, coated with the sheen of insensibility and death. He lay quietly upon his back, very straight, without any sign of pain, and with a curiously upturned thrust of his sharp thin face. His mouth was firmly shut.” Through the night Wolfe kept vigil over his dying brother. He prayed, “Whoever You Are, be good to Ben to-night.” Wolfe fell asleep for a while and then awoke suddenly and called his family into his brother’s room. “[Ben’s] body appeared to grow rigid before them. Ben drew upon the air in a long and powerful respiration; his gray eyes opened. Filled with a terrible vision of all life in the one moment, he seemed to rise forward bodily from his pillows without support—a flame, a light, a glory...[Ben] passed instantly, scornful and unafraid, as he had lived, into the shades of death.” In Rochester “When the Spanish Influenza epidemic invaded Rochester in the fall of 1918, the community was paralyzed. Military demands of World War I have steadily drained the area of trained nurses...the epidemic prostrated nearly 13,000 Rochesterians, at its peak killing thirty to forty victims a day...as many as 800 a day collapsed with chills and fever...they were parents and teachers on whom Rochester’s children depended and the workforce on whom Rochester’s businesses and factories relied....In mid October, when 400 to 600 new cases appeared each day, the city closed down; schools, stores, factories, theaters, taverns and even churches were ordered to suspend all activities. In one home the father and mother were both powerless to do anything because of the force with which influenza had seized them. Their two little children, 5 and 7 years old, could not be cared for. Although there was plenty of coal in the house there was no one to build a fire. Rochester General and other area hospitals were caught shorthanded with many of the graduate nurses working in American Red Cross military hospitals outside the area. The operating rooms were closed ‘on account of the danger of contamination.’ The fifth floor was converted into an influenza ward along with one of the medical annexes in the rear of the hospital. Beds were set up in every available space to handle the increased patient load. Before the end of the epidemic five months later, over 870 patients would be treated including 80 students. Some 160 patients died from the flu or pneumonia related causes. In Brockport Another item on November 7 read: REPORT ON INFLUENZA EPIDEMIC WORK OF AUTHORITIES ——— Few of Population Affected and Mortality of Only Three Persons Although the public realizes that the village authorities have been active in the attempt to limit the spread and to ensure relief for those afflicted, the committee feels that a brief history of the epidemic and of its management will be of interest to the citizens. On Sunday, Oct. 13th, church services were abandoned at the request of the health authorities and on the evening of that day a meeting was held at the trustees’ rooms attended by the village and town boards, the health officer and village attorney, the clergymen of the various churches, representatives from the village and rural schools, the editors of the local papers, the health officer of Clarkson and representatives from several industries in the village. At this meeting an emergency ordinance was discussed and enacted, becoming effective immediately and copies of this ordinance, together with advise to the public were distributed to every household on the following day, the Boy Scouts doing the larger part of the distribution. At the meeting of the village board on Oct. 14th, Mr. Henry Lathrop was appointed special sanitary officer and has served throughout with great efficiency in instructing in preventative measures. Inspecting industrial establishments and places where food or drinks were served and in general endeavoring to secure compliance with the ordinance. During the first few days Miss Lawton also of the Normal School faculty assisted Mr. Lathrop in his work. During the first week the cases increased rapidly, the number rising from 9 on the 13th to 71 on the 19th. On the 19th Dr. Chapman was forced to give up to a severe attack of the disease and his death a few days Eunice Chesnut of the Western New York Historical Society found in her notes: Dr. Edward B. Chapman, (1882-1918) began his medical practice in Brockport on King Street in 1907. He later opened an office at 138 Main Street adjacent to the Catholic church. Influenza today Scientists have long known the possibility of another pandemic sweeping the earth was not only possible, but likely. The bird flu, or avian flu as it is sometimes called, that is making news these days could be it. Or not, depending on many conditions. The bird flu popping up around the world scaring epidemiologists this year so far only infects birds. With only a few exceptions (about 100 cases in Asia) humans do not fall ill from this strain of bird flu, and birds themselves show no sign of illness. What worries public health officials is that this year’s bird flu -- or next year’s -- might mutate in the same way “Spanish Flu” did and infect humans causing another pandemic. Learning from the dead Researchers have not been able to study history’s deadliest disease-causing organism until unearthing the Alaska sample because there were no viable samples of the “Spanish” influenza virus. Experiments began in August and have already revealed that the 1918 virus was a bird flu type that appears to have become infectious to humans through slow multiple mutations. Some of this year’s bird flu, identified as the H5N1 strain, appears to carry a few of the mutations seen in the 1918 virus contributing to the fear that it may evolve into a virus infectious to humans. Researchers hope studying the resurrected Spanish influenza virus leads to better vaccinations and drugs. In 2005 According to the Center for Disease Control, influenza activity so far this season is low in the United States. The proportion of patient visits to sentinel providers for influenza-like illness and the proportion of deaths attributed to pneumonia and influenza were below baseline levels. New York State Department of Health recommends when there is an adequate supply of vaccine, everyone should get the flu vaccine. Those people at greatest risk for complications of the flu and those most likely to get or spread the flu should be immunized as soon as vaccine is available. These include: •All children aged six to 23 months From the writer’s perspective: “Curiosity struck me while researching the Markham family history with the deaths in 1918 of two young adults. A little reading revealed their probable cause of death and the impact of the 1918-19 influenza pandemic on nearly every family everywhere in the world. The photos of headstones in local cemeteries are those of lives ended in 1918--probably by the flu. At the time of my initial research it was an untold story. Only recently have books about the pandemic been published and recollections gathered. My early research was for a documentary pitched to "The American Experience" program at WGBH which ultimately made a film about the pandemic, but without my involvement. It's a fine film patched together with photos from the National Archives at the Library of Congress.” "Influenza 1918" narrated by David McCullough is available for rent or loan at local libraries. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/influenza/ November 20, 2005 |