Local Marine remembers Iwo Jima

by Rick Stacy

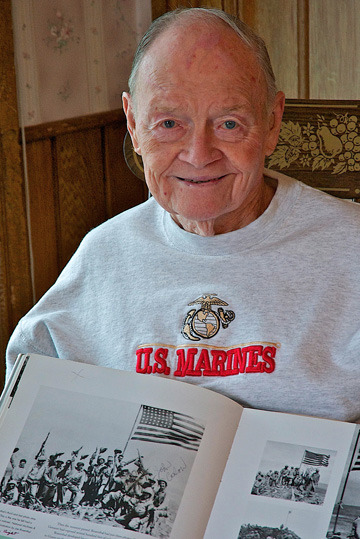

Bergen resident John Conlon, a Marine Private First Class at the battle of Iwo Jima, holds open a page from Eric Hammel’s book “Iwo Jima: Portrait of a Battle: United States Marines at War in the Pacific” showing a group photograph taken on Mt. Surabachi by Pulitzer prize-winning photographer Joe Rosenthal. The photo was taken after Rosenthal’s iconic flag raising image. Conlon is fourth from the right. Photograph by David Knox.It’s March 18 and John Conlon is celebrating his twenty-first birthday. The year: 1945. The place: the black, volcanic sands of Iwo Jima. He hasn’t bathed, shaved or had a hot meal in almost a month. He has already charged up Mt. Suribachi, whose summit was the site of a flag raising that became the iconic symbol of Marine’s victory for all time. Conlon had watched it go up.

Bergen resident John Conlon, a Marine Private First Class at the battle of Iwo Jima, holds open a page from Eric Hammel’s book “Iwo Jima: Portrait of a Battle: United States Marines at War in the Pacific” showing a group photograph taken on Mt. Surabachi by Pulitzer prize-winning photographer Joe Rosenthal. The photo was taken after Rosenthal’s iconic flag raising image. Conlon is fourth from the right. Photograph by David Knox.It’s March 18 and John Conlon is celebrating his twenty-first birthday. The year: 1945. The place: the black, volcanic sands of Iwo Jima. He hasn’t bathed, shaved or had a hot meal in almost a month. He has already charged up Mt. Suribachi, whose summit was the site of a flag raising that became the iconic symbol of Marine’s victory for all time. Conlon had watched it go up.

“My outfit, Fox Company, was already up there,” recalls the eighty-seven year old Bergen resident. “They decided that the flag they had raised up first wasn’t big enough so they got a bigger flag. After they put the flag up, Rosenthal, the photographer, said, ‘Come on now boys, gather around and get your picture taken. The people back home like to see what the boys are doing.’ And that’s the way I got in the picture.” This picture of Conlon and others from Fox and Easy Companies in front of the famous flag was taken right after it was raised. Conlon is fourth from the right, with his rifle raised. Most of the men in that picture never made it home.

“On the third day the flag was raised,” says Conlon. “Everybody clapped and everybody yelled. But there was a lot of war going on after that. We were supposed to take the island in 72 hours. It took 36 days! Before we went in, the Navy blew the place. The Air force blew the place. But the Japanese, some 22,000 of them, were down in the ground. There was forty miles of tunnels. They just watched us in there and laughed at us. From all the bombing they killed two hundred men at most.”

On Ship

Conlon wrote his mother while still on the ship and said he didn’t know if he’d live to be 21 or not. His general gave him some advice: ‘John,’ he said, ‘when you get off the ship I want you to look right straight ahead and don’t turn around, just keep right on going. Don’t stop to help anybody. Don’t make any buddies because when you do, you help your buddy and lots of time you’re gonna get killed with them.’ And that’s what I did on Iwo Jima,” says Conlon. “I never got close to anybody. I did what I was told. And to this day I’ve never had a (close) man friend. But I lived.”

But on the ship, Conlon had a friend in his platoon, Les, who was from Niagara Falls. “He was close to me, this fella,” says Conlon. “When we were climbing down the ship’s ladders to the Higgins boats to get to the beach, he said to me: ‘John, I’m never gonna live through this. I want you to go to Niagara Falls and see my parents when you get home.’ I said, ‘Oh what are you talking about. You’ll be fine.’ Well, the flag was raised on the third day, and Les was killed on the sixth day on the beach. He stepped on a mine. The beach was loaded with mines. It blew him into a million pieces.”

About ten years ago all the bodies that were buried in Iwo Jima were exhumed and brought back home. Les’s body was brought back to Niagara Falls to be buried. Conlon was one of his pallbearers. “I did what I told him I’d do,” says Conlon.

Hitting the Beach

Marine Pfc. John Conlon in 1945. Bergen resident, John Conlon, a Marine Private First Class was a member of the 2nd Battalion, 27th Marines, 5th Marine Division at the battle of Iwo Jima.Conlon doesn’t recall why he chose to become a Marine. “I just don’t know to be truthful about it,” he says. “I was working in a slaughterhouse in Byron with my dad butchering cattle and I hated it. I just wanted to get away. And my mother took me down to Rochester and I enlisted.”

Marine Pfc. John Conlon in 1945. Bergen resident, John Conlon, a Marine Private First Class was a member of the 2nd Battalion, 27th Marines, 5th Marine Division at the battle of Iwo Jima.Conlon doesn’t recall why he chose to become a Marine. “I just don’t know to be truthful about it,” he says. “I was working in a slaughterhouse in Byron with my dad butchering cattle and I hated it. I just wanted to get away. And my mother took me down to Rochester and I enlisted.”

But slaughtering took on a new meaning for Conlon on Iwo. It was some of the fiercest fighting of the Pacific theater of the war with more casualties than the total Allied casualties on the D-Day invasion. Over 19,000 Marines were wounded and almost 7,000 killed taking the island.

Conlon landed with the 2nd Battalion, 27th Marines, 5th Marine Division, and was the fourth or fifth wave in. “We went in on Red Beach One. That’s right at the foot of Mount Suribachi. There was some shooting going on but nothing much. From there on, things were quiet in the morning –real quiet. I lay there on the beach, all morning. The general of the Japanese had gone to school in our country,” Conlon says. “He told his men not to fire. ‘Let them all come in the beach and when I give the word you open up,’ he said. When noon came they opened up on us and you never saw so many dead bodies in your life. They killed thousands of Marines that first afternoon.”

“There was a Marine that came over from the states. He had all kinds of hashes and stripes on his uniform. A big, handsome man,” Conlon recalls. “He was so gung-ho. Boy he rode our ass on the ship. He’d put a white pair of gloves on and inspect your rifle and if there was one spot on it he made you clean it for a week. He was so mean. He’d say: ‘If the Japs don’t kill me my own men will.’ He knew that he wasn’t doing right. I felt so sorry for him that he had to be like that. Well, when we hit the beach who do you think was the first guy I seen up in front of me that was dead? It was him. He had a bullet right there (points to forehead). Do you know I cried? I lay beside him for three hours because the shooting was so bad. He was in the way of the bullets. He was protecting me. I put my arm around him and I laid there until the bullets slowed and then I moved. I opened his pocketbook and he had a picture of his wife and a little boy and girl. I said, ‘He’ll never see them again. Daddy’s not coming home any more.’ That was so sad. I never felt anything that hurt so.” Even these many decades later, Conlon pauses, overcome by the poignant emotion of that memory. “Why couldn’t he have been nice?” he says. “Why couldn’t he have been nice. He had had a diamond ring on him that was a big as his whole finger. It just sparkled. Well somebody had come along and cut that finger right off. It was gone.”

Moving up Mt. Suribachi

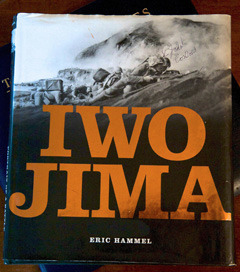

Marine Pfc. John Colon’s favorite photo of himself taken during the battle of Iwo Jima is on the cover of Eric Hammel’s book “Iwo Jima: Portrait of a Battle: United States Marines at War in the Pacific.” Photograph of book cover by David Knox.During Marine training at Camp Pendleton, Conlon had scored second highest in his outfit on the machine gun. “Course there were others better than me. They were all crack shots,” he says. On Iwo Jima he was a rifleman. “I went in with a M-1 (Garand) . They weigh about eight pounds.” Conlon pulls out a large book on Iwo Jima and points to the cover which shows an alert Marine crawling up Mt. Suribachi. “That’s me on the cover,” he says. “The sand was probably two feet deep all over the island from the volcanic ash. Of course your shoes are all full of sand. And the island was so hot. No matter where you put your hand on that island it was hot. You could take your hand and scoop out a hole and set your C-ration can in it and it’d warm it right up.”

Marine Pfc. John Colon’s favorite photo of himself taken during the battle of Iwo Jima is on the cover of Eric Hammel’s book “Iwo Jima: Portrait of a Battle: United States Marines at War in the Pacific.” Photograph of book cover by David Knox.During Marine training at Camp Pendleton, Conlon had scored second highest in his outfit on the machine gun. “Course there were others better than me. They were all crack shots,” he says. On Iwo Jima he was a rifleman. “I went in with a M-1 (Garand) . They weigh about eight pounds.” Conlon pulls out a large book on Iwo Jima and points to the cover which shows an alert Marine crawling up Mt. Suribachi. “That’s me on the cover,” he says. “The sand was probably two feet deep all over the island from the volcanic ash. Of course your shoes are all full of sand. And the island was so hot. No matter where you put your hand on that island it was hot. You could take your hand and scoop out a hole and set your C-ration can in it and it’d warm it right up.”

“You see the guy behind me (He points again to the book cover.) He was killed. I took his rifle and threw the other one down. He had a Carbine and his had a lot more ammunition in it. It was lighter and you could throw it right over your shoulder and get away from all that weight. After the shooting started I got rid of my pack, it weighed seventy pounds. I got rid of everything,” says Conlon.

At first he wasn’t catching any fire because he was down low. “The bullets were going right over me. But the closer you went in the more fire you got,” he says. What was going through his mind at that point? “I don’t know what I was thinking. I know I was darn busy, but I never had the fear of death. I believe the Lord was walking right beside me. I really believe this.”

“My buddy Pete and I were going up the mountain and all of the sudden he dropped down. He had a bullet almost cut his right ear off. My shoulder was right next to his. It only just missed me. It threw his helmet on the ground and ripped his ear right off. The Navy Corpsman was right there and he patched him up and that was it, he went back on the ship, the lucky dog. The Corpsman who helped him was John Bradley, one of the ones who raised the flag,” Conlon says.

“The Italians were the best fighters we had with us, them and the Indians,” recalls Conlon. “There were only four Indians but they were Cracker Jacks. They have a certain gift. I had one Indian in my battalion, Ira Hayes, a little Indian. He’s in the big monument (in Washington, D.C.). He’s the one that raised the flag.” Conlon didn’t like the movie about the flag raising ‘Flags of our Fathers’ because it wasn’t true to form. “The portrayal of Ira Hayes was not true. He was only about five foot high. Very humble. He was quiet, real quiet. Then he got drunk and you couldn’t shut him up. But he enjoyed life. We were over in Hawaii on Maui, that’s where we were before we went to Iwo Jima. Ira Hayes would go out every Sunday and get drunk downtown. Then he’d get on the four corners and start directing traffic, a crazy guy. The MP’s would put him in jail and the guys would have to go down and pick him up. But he was a peach of a guy. You know what the best movie was? It’s the one with John Wayne (Sands of Iwo Jima). That was just about the way it was.”

Burial Duty

After a few days Conlon was put on burial duty. “Right away there were bodies all over the place. They had to get them in the ground. They gave me forty Marines to bury. We had to go out and pick up the bodies in an Amtrak. We had to go all over the island to get them, up on the mountains, everywhere. I was in charge of that. We buried them in mattress covers –a great big cemetery. They had a bulldozer dig a trench and they laid them there side by side,” Conlon says.

“There’s so much work to that,” he says. “You take their rings off and all their possessions and everything was put in bags. The bodies all had to be finger printed. Then they spray them with a spray you know because it was so hot and there were the maggots. You know what I couldn’t understand? They claimed there was no bugs or bees or anything on Iwo Jima. There wasn’t a tree or anything. So how could you get maggots on a body with no flies? But every time you picked up a body, maggots would just drop right off, if it lay there very long.”

“There was a guy called John Basilone. Basilone was the greatest hero that ever lived. At Guadalcanal, I forgot how many Japs he killed. He got the Congressional Medal of Honor. One day while on burial detail, I’m standing there and they come over and they put a body right at my feet. They said, ‘John, do you know who this is?’ I said, ‘No not really.’ ‘That’s Basilone,’ they said. ‘Oh My God,’ I said, ‘you mean to tell me that he got killed?’ He was one of the first ones to hit Iwo Jima on Red Beach 2. He had a baseball hat on and carried a 45. He had said, ‘There ain’t a Japanese bullet that can pierce my body.’ Well, it wasn’t a Jap bullet but it was something worse. When they landed, Basilone said, ‘We’ve got to get the guns off the beach.’ Well it was just a matter of minutes and up he went. He was hit by a mortar. It blew him all to hell with four or five other Marines.”

“There were so many mines,” Conlon recalls. “We’d go around and try to find them. Once, I was walking along the beach and this guy was hit by one. He was right in front of me. It took his right leg completely right off. On his leg was half his rear end. It lay over there like a hind quarter of beef. We put twenty packages of sulfa on his wound to stop the bleeding and everything. He said to us: ‘At least I’m gonna get the hell out of here.” I often wondered if he survived. They’d take the wounded to hospital ships, two or three great big ships out in the ocean. I mean you are talking about thousands of guys wounded. Thousands! There was just a stream of guys headed down to the beach walking toward the ships –if they could walk.”

Claiming the Island and Clearing Caves

Cave by cave, tunnel by tunnel, Conlon and his fellow Marines took control of the Island. Sometimes they used dogs to flush out the Japanese. “When you were asleep, that dog was awake. But you don’t sleep,” adds Conlon.

Conlon ate and slept, when he could, in the field. “I was pretty scrubby looking. All I ate was C-rations and K-rations. I had nothing. I got rid of my pack right on Red Beach One. All my clothes were in it. Everything was in it. I was trying to save my life. I didn’t need all that excess,” Conlon says. “All hell is breaking loose all the time. The bullets never stop. At night they throw up those little parachutes with flares to see. But the Japanese were so sneaky. I’d hear them hollering: ‘Hey Joe, Hey Joe.’ They were trying to draw you over. It was always ‘Joe.’”

“One night, this Marine got way ahead of us. I don’t know how the hell he got there, but they got him. He probably stepped in a cave to get out of the rain. But he screamed and yelled all night. We tried to get to him up there. We were sitting on one side of a cliff, the water was dripping down on top of us, a creepy place. But you could hear him in the distance screaming and yelling. Three or four other Marines tried to get to him. One was killed and another was wounded trying to get to him. He screamed and screamed all night. The next morning we went up and went in the cave and there he lay, on his stomach. They had taken a bayonet and cut big chunks of meat out of his butt and his back. Big chunks of meat! They took his wrist and they twisted it right off until it just hung down. Tortured him terrible. He had red hair. I would say he was probably twenty. The poor thing. And then they put a bullet in him right there (points to head), to give him a break from the pain. That poor thing went through hell. After that we never took anybody prisoner. We killed everybody. Before we used to let them surrender if they wanted to surrender. After that we killed everybody. That was it. There was nobody going to be left alive when we got done,” says Conlon.

“I probably killed about thirty-seven Japs, that I know of,” says Conlon. “That’s not a lot, not when there’s twenty-two thousand there. I never liked killing anyone. If I didn’t have to, I didn’t. He had a mother too. In other words, if I didn’t have to kill him, I let somebody else do it. I’d kind of look the other way. I mean, I could kill anybody, but it’s just the idea of the thing, you know? After all, he was just there doing a job. And as for that guy that was tortured, that was just an incident. It kind of fired everybody up. Everyone didn’t see him lying there with chunks of meat missing. It was just five or six of us. There are so many things that happen in war. That was the first war I was ever in.”

Flame-throwers were used to flush the Japanese out of the caves. “They even had flame-throwers on the tanks,” says Conlon. “A guy had a flame thrower on his back and was clearing out a hole and he just missed me. It was pretty hot. It really scorched me.” Conlon pulls up his sleeve revealing the scars on his arm.

They went through the caves only once. “We’d find all kinds of barrels of sachi, and kimonos left there from the prostitutes that had been there. The prostitutes had left before we got there. But toward the end they were all hungry and there was no water and they were happy to come out. They just surrendered. They about had it. They were happy it was over,” he says.

Bringing in the Planes

Once the island was coming under control, the planes that were returning from their bombing runs were able to land. “The Navy Seabees (Construction Battalions), they did a lot of work on the island. They took care of the airfields and everything. They built all that. They were the best. They were working right there under fire. They had to get the airfield done because that was what the fighting was all about,” says Conlon. “One day a guy was running a small bulldozer up on the beach. He hit a mine. It took that bulldozer and put it upside down. The guy on the seat got thrown right off and he lay there, blood was coming right out of his eyes. I don’t know if he lived or not.”

“There was always four Mustangs that would follow a B-29 and one would land at a time. Boy they were a great plane,” Conlon recalls. “Some of those B-29’s coming in crashed and burned. One guy came in and landed his plane and said, ‘Thank God for the Marines,’ because the ocean was full of B-29’s and Mustangs that didn’t make it back. They ran out of fuel or were shot up and their plane was damaged. They needed Iwo Jima to land on. We took Iwo Jima so they could land there short.”

“The B- 29 crews, when they landed, they put up their tents. We had just gone back to the ship. The Japanese came out and got after the pilots at night and chopped them all up with swords and cut all their tents up. We had to come off the ship again and clean that up. That was a mess. You see, your not going to kill all those Japs, there were so many tunnels. There’s gonna be some left there. There probably is today,” Conlon adds with a smile.

Upon reflection, Conlon feels they should have never taken the Island in the first place. “When we got back into Hawaii, there was only a half a dozen of my company that was left. It came over the radio that Franklin D. Roosevelt had just past away. Well then Truman was put in. Truman was tough. Truman used the atomic bombs. If they had waited just a little bit longer, see, Iwo Jima would’ve never had to be taken at all, cause that ended the war. It was really a tough thing, but it ended the war,” he says.

Saddle Up

“They dropped the atomic bomb and that ended the war, otherwise it’d probably still be going yet,” Conlon says. “That’s when they sent us to Japan. I was there for a year. Got things all straight over there. The first thing, we pulled in with the train loaded with Marines and right beside us was a Japanese train. We reached out and shook each other’s hands. They were happy the war was over.”

“We took over a Japanese camp over there. They built a nice little building and six of us took that building over and we all took turns taking care of the boiler. It was good duty. Every day there was ten Japanese that came in and picked up all of the papers, cleaned the showers and did whatever needed to be done. Nice guys. They thought the world of me. They loved the American soap, they’d always grab a hold of that,” he says.

“Then there were the guys who fell in love with some of the Japanese girls. I tell you, some of them Japanese girls were beautiful and they could speak good English. Frank, a little Italian guy, he went with this Japanese girl and she was absolutely beautiful. And they were in love. I remember when it was time for us to leave, she said: ‘Bye Franky, don’t leave me, don’t leave me.’ And that’s the last he ever heard of her. I stopped down to see him one day when we were back and I never saw anyone so depressed. I mean, why didn’t he send over for her?” Conlon says.

“But there were a lot of girls who were pregnant from the (American) guys, from the Marines and the Army. And that’s always the way, in Germany, in France, that always happens,” he says.

While in Japan, Conlon became friends with some Japanese who had a stable of horses. He has always loved horses. “I raced horses for years,” says Conlon. “I had 16 horses racing at one time. In fact I have good one racing now His name is Yankee Ben. Boy he can trot,” he says.

“These Japanese had some beautiful horses,” Conlon recalls. “They had everything. They had a regular stable, saddles and everything. Since I had this nice job taking care of the boiler, and I had all these other men to help, I could go out everyday and ride horses. I had a couple horses I taught to jump over there.”

“You know it’s been a lot of years since I was there,” says a thoughtful Conlon. “But all the time I was in Japan I never saw one thing out of the way, by either one of us. With the Japanese we got along just fine – with everybody. I never saw anything that went so smooth.”