Up from the South

Remembering those who came before

by Riga resident Fleda Gibbs

Grandmother Fleda (born 1868) managed to pursue education and received a certificate for teaching at one of the black colleges, writes Riga resident Fleda Gibbs.

Grandmother Fleda (born 1868) managed to pursue education and received a certificate for teaching at one of the black colleges, writes Riga resident Fleda Gibbs. Fleda GibbsIn her own words, Fleda Gibbs recounts the early years when her parents moved north to settle in Rochester.

Fleda GibbsIn her own words, Fleda Gibbs recounts the early years when her parents moved north to settle in Rochester.

With their meager possessions strapped to the top and back of our uncle’s old automobile, our young parents, Lulu and Lincoln Jackson, along with their young son, struck out from Silverstreet, South Carolina in 1929; following in the path of Lulu’s older siblings who had made the trek north years earlier, seeking a better way of life in Pennsylvania and New York state.

What did this couple find in their new environment in Rochester, NY? A well constructed house with electricity, a large kitchen, clean drinking water, a gas stove for cooking and an icebox.

In the cellar, a coal-burning furnace for warmth in Rochester’s cold winters. Upstairs, a bathroom with a sink and large bathtub and a flush toilet! Hallelujah! The couple was elated!

There were also in place dedicated church women who garnered items: used clothing, bed linen, quilts and foodstuffs for individuals and families arriving in Rochester. They knew they had to take care of their own people and this they did.

Most important was medical care readily available to my parents and the colored community during the 1920s – 1950s in Rochester. Two Rochester physicians, Dr. Anthony Jordan and Dr. Charles Lunsford, along with dentist Dr. Van T. Levey, were pioneers in health care, administered to Rochester’s colored population.

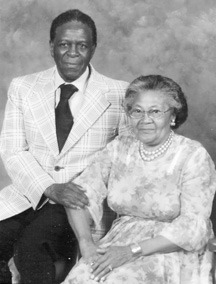

Lincoln and Lula Jackson struck out from Silverstreet, South Carolina in 1929 for a new home in Rochester. Years later, with the hunger for their own land, they moved to Riga and raised a family there.Dr. Jordan delivered my sister, Addie, in 1938 and he diagnosed rickets in my brother, DeLeon, about a year later, in 1939. Mama would line up the children in her bedroom and each would have to swallow the most nasty tasting cod liver oil.

Lincoln and Lula Jackson struck out from Silverstreet, South Carolina in 1929 for a new home in Rochester. Years later, with the hunger for their own land, they moved to Riga and raised a family there.Dr. Jordan delivered my sister, Addie, in 1938 and he diagnosed rickets in my brother, DeLeon, about a year later, in 1939. Mama would line up the children in her bedroom and each would have to swallow the most nasty tasting cod liver oil.

At 124 Genesee Street, my parents were one block from St. Mary’s Hospital (Bull’s Head) on West Main Street. Further along West Main Street was Rochester General Hospital at Prospect and Troup Streets. These two medical facilities, within walking distance of their residence, provided them with comprehensive health/emergency care which was not readily available to them in Silverstreet, South Carolina.

The Succi (mature woman versed in treating ailments) did what they could as first responders for minor health/emergency problems; but they had at their disposal primitive tools (herbs, leaves, roots) for making poultices and teas.

Grandmother Fleda (born 1868) managed to pursue education and received a certificate for teaching at one of the black colleges. She was not permitted to enter the public library where she taught. Negroes were not allowed. Miss Fleda would write items she needed for teaching her classes and give this list to a friendly white lady. The lady secured the items and brought them to Miss Fleda. She returned the items in the same manner.

Settling down

Along with these glorious finds, what else was in store for these two? Was it the haven they sought? Not quite.

Dad worked as a laborer, “tying steel” for the wings atop the Times Square Building on Exchange Street, downtown Rochester. Afterward, he worked on a building at the University of Rochester. He remembered there being only one building on campus then.

A couple of his buddies, rather than walk the long distance across Ford Street bridge to the work site at the U of R, foolishly crossed the frozen Genesee River. “I never did,” Dad said.

Dad was assigned to work for the city in the Department of Public Works (DPW), collecting the city’s garbage. This was in the 1930s. At that time, garbage was collected by wagon, pulled by a team of large work horses. The city’s waste was collected and hauled to the transfer station at Lower Falls. The work was hard and dirty. Younger men were assigned to carry trash cans from the rear of each house to the wagon at curbside, where a man inside the wagon dumped the trash and returned the can to the ground man. Dad said dead animals – dogs, cats, etc. – were covered with maggots, the stench of which was horrendous. Some of the workmen smoked to cover the stench.

Dad had a full load of garbage as he entered Platt Street Bridge in 1938. The old, single-lane wood bridge had low wooden railings. Whooa – Dad steadied the team as a black sedan entered the bridge from the opposite direction. Someone of importance, no doubt. Someone had to back up. Dad held the team in check, foot firmly on the wagon brake.

Lo – here comes a motorcycle cop who yelled out orders: “Back up that wagon – let this car through!” Dad held his ground, did not attempt to back up. There was a stand-off. Dad knew that any attempt to back the horses on this narrow bridge, with a ton wagon loaded with a ton of garbage was impossible! (As any farmer can attest to).

Had an attempt been made to back up the horses, the wagon would have jack-knifed, the weight of the wagon and garbage being hurtled over the low railings into the air, with horses thrashing, all to explode hundreds of feet into the gorge below. Dad held his ground.

Finally, the entity in the automobile gained a semblance of common sense and backed up. The cop, his authority challenged by a black man sitting atop a wagon of stinking garbage, sped off. And my father lived.

I was a young woman (1980) in my car in the middle of Clinton Avenue, with Sibley’s on the right. There was a traffic officer motioning me to make the left turn. I did not make the left turn, I waited. The officer yelled at me, “I told you to turn.” Had I turned, at his orders, I would have run over a couple crossing the street at that exact moment. He obviously did not see them.

One has to choose, instantly sometimes, whether to obey an order or desist. It could mean someone’s life.

The Streets

Dr. William Street and his wife, Lola with Lulu Jackson. Thanksgiving dinner at their apartment #101 Gibbs Street.Early in the 1930s a church member expeditiously made his way to Lincoln’s home. And excitedly informed him that, “They are getting up a petition to put you out of your house.” “They,” residents in the area, did not want a colored family living in the neighborhood.

Dr. William Street and his wife, Lola with Lulu Jackson. Thanksgiving dinner at their apartment #101 Gibbs Street.Early in the 1930s a church member expeditiously made his way to Lincoln’s home. And excitedly informed him that, “They are getting up a petition to put you out of your house.” “They,” residents in the area, did not want a colored family living in the neighborhood.

Mrs. Jackson became acquainted with Dr. William Street and his wife, Lola. Dr. Street was a teacher of percussion at Eastman School of Music. He and his wife, Lola, were prominent in political and social affairs in Rochester.

One summer afternoon, a shiny Packard car pulled up to the Jacksons’ home. Out stepped Dr. Street and Lola, meticulously dressed in summer whites and wearing stylish hats. Dad said neighbors stared from behind curtains and front porches. On their lips, “Why is this wealthy white couple going into the home of colored people?”

The Streets were mentors and advocates for my parents. Mother worked for them as housekeeper. I joined Mama cleaning house when a teen. They were instrumental in the Jacksons remaining in their home and living a comfortable, dignified life. The Streets moved from their home near Genesee Park Boulevard to Gibbs Street, a block away from Eastman School of Music. Mama worked for the Streets almost 30 years, until their deaths. These many years later, I became aware of just how much this amazing couple contributed to my parents’ well-being. I shall never forget these two dear people.

Did Lincoln and Lulu find the better way of life they were seeking in 1929? Absolutely. Though they grew up amidst turmoil and racial strife in the South, they persevered. With kindness and generosity of many people in Rochester and Riga, they thrived. They remained cheerful and happy throughout the rest of their days. Dad became employed at East Rochester Despatch, later to be named East Rochester Car Shop. He retired from there in the 1970s. He had accumulated good retirement benefits. Something which would not have been available to him in South Carolina.

I honor those who came before me: aunts, uncles, cousins, grandparents, great, and great-great for their service, sacrifice, and unwavering endurance – these were great soldiers on the battlefield of life. As for my parents Lincoln and Lulu Jackson, they certainly made the right decision by moving up from the South.

Making Riga home

The Jackson children attended Riga District School #8.When my parents first moved to Riga they had to readjust to a house with fewer amenities for a time. They wanted the land to grow food and to be able to have a cow, chickens and such to allow then to be more self-sustaining.

The Jackson children attended Riga District School #8.When my parents first moved to Riga they had to readjust to a house with fewer amenities for a time. They wanted the land to grow food and to be able to have a cow, chickens and such to allow then to be more self-sustaining.

Our family has good neighbors and long-time friendships in Riga for these 71 years. I remember with great fondness: Judge Clarence Haller, Clyde Dick and his wife, the Pimm family and Ralph Kendall, DDS, as well as Dr. Vail and Dr. Dietl. I shall never forget the wonderful and gracious teacher Nina Malloch. Our beloved Prof, Gordon Taylor, music teacher who became vice-principal and later principal of Churchville-Chili High School. Lest we forget Alice Campbell Taylor, teacher and wife of Prof. Taylor who showed such kindness and compassion when she visited our folks after the death of our brother, John H. Jackson. Alice Taylor also visited our mother while she was in Wesley Garden Nursing Home in Rochester. Always to be remembered with affection, John Ames (AKA “The Whistler”), basketball player, and close high school buddy of our brother John H.