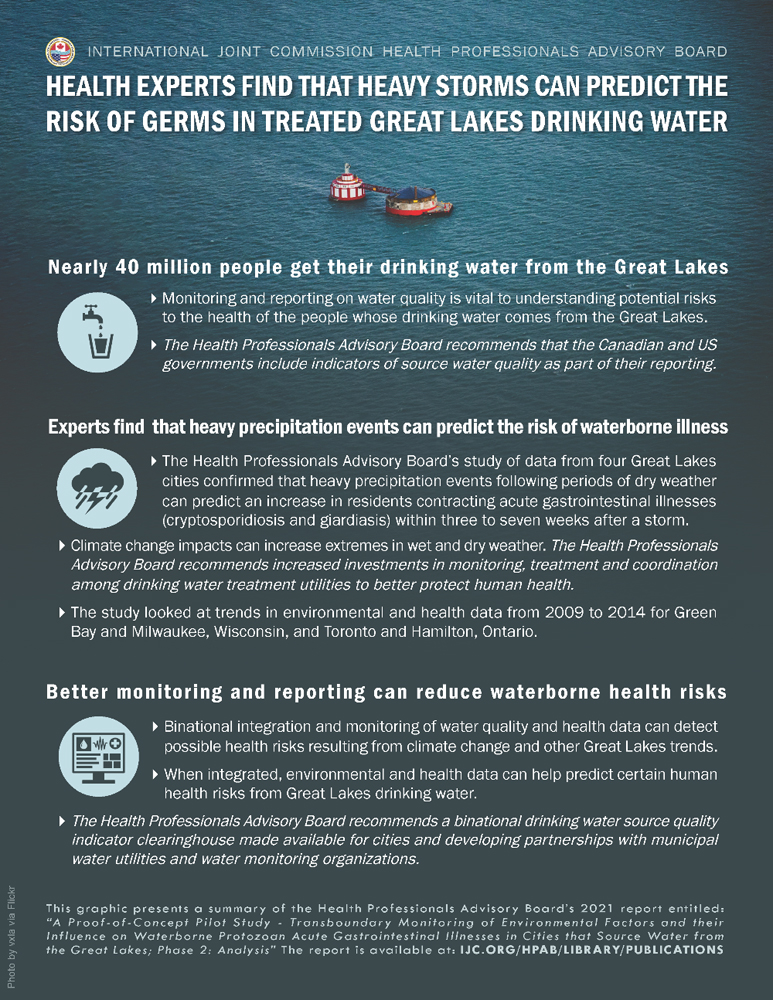

Health experts find that heavy storms can predict the risk of germs in treated Great Lakes drinking water

Across the Great Lakes basin, hundreds of water utilities treat water from the Great Lakes and deliver safe, high-quality drinking water to nearly 40 million residents. The risk of getting a stomach bug from this treated drinking water is very low – but there is some risk. A new study of environmental and health data from four cities in Canada and in the United States shows that the risk of getting sick from treated Great Lakes drinking water can increase after certain weather events.

The Health Professionals Advisory Board of the International Joint Commission recently published their findings in a new Phase 2 report on their proof-of-concept pilot study “Transboundary Monitoring of Environmental Factors and their Influence on Waterborne Protozoan Acute Gastrointestinal Illnesses in Cities that Source Water from the Great Lakes.”

The study looked at health, weather, and water quality data for the cities of Hamilton and Toronto, Ontario (on Lake Ontario) and Green Bay and Milwaukee, Wisconsin (on Lake Michigan). The study found a link between heavy precipitation and public health: no matter the season, more people got stomach bugs a few weeks following a big storm.

“The data show that there is a consistent pattern: no matter what time of year, if it was dry and then there was heavy precipitation, about three to seven weeks afterwards there were more reported cases of people getting sick from either of the two waterborne germs we were tracking, giardia and cryptosporidium,” said Dr. Elaine Faustman, US co-chair of the board, professor and director of the Institute for Risk Analysis and Risk Communication at the University of Washington.

The pattern of heavy precipitation preceding the increased risk of acute gastrointestinal illness points to gaps in monitoring and reporting on the Great Lakes as the source of treated drinking water.

“One of the big challenges doing this study was that the data were scattered across many agencies, and so one of the board’s recommendations is to have a binational clearinghouse of these data indicators,” said Dr. Laurie Chan, Canadian co-chair of the board, professor and Canada research chair in toxicology and environmental health at the University of Ottawa. The board was assisted by the cooperation of water utilities and public health agencies in the four study cities that provided the requested data.

The board chose these four cities for the study with the purpose to compare two major cities on the same lake, for two lakes, with one pair in Canada and the other in the United States. The study did not compare data with any other metropolitan areas or smaller communities on other lakes.

“Our proof-of-concept study demonstrated that, when available, these data are good indicators for the health safety of the Great Lakes as our drinking water source. Public health can be better protected with greater monitoring and reporting on source water quality, as well as with increased investments in surveillance and treatment infrastructure,” said Dr. Seth Foldy, report co-author, member of the board and former director of epidemiology, informatics and preparedness at Denver Public Health.

“Climate change is expected to increase extreme rain events in the Great Lakes which, particularly after a dry period, can increase the risk of waterborne illness from drinking water. So, it’s imperative that governments address gaps in monitoring to reduce that health risk to the public,” said Dr. Tim Takaro, professor of health sciences at Simon Fraser University who served as the Canadian co-chair of the board from 2015 to 2020.

A graphic executive summary of the report findings is available at ijc.org.

Provided information