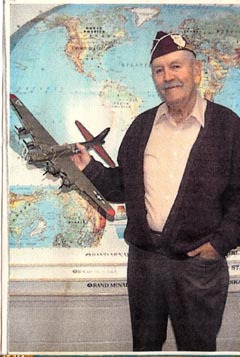

Mission 26: A WWII POW’s story

by Rick Stacy

It was a clear, sunny August day over Germany as B-17 Bomber pilot, Bill Rohrbacher, led his squadron toward Berlin. Their target was an engine factory. His typical crew of ten men was one heavy — they were breaking in a rookie navigator. It was Rohrbacher’s 26th bombing mission — four more and he could go home. But fifty miles from the target the blue skies suddenly filled with black puffs of exploding flack.

It was a clear, sunny August day over Germany as B-17 Bomber pilot, Bill Rohrbacher, led his squadron toward Berlin. Their target was an engine factory. His typical crew of ten men was one heavy — they were breaking in a rookie navigator. It was Rohrbacher’s 26th bombing mission — four more and he could go home. But fifty miles from the target the blue skies suddenly filled with black puffs of exploding flack.

The number three engine on the right side of the plane was hit first. Then the number four engine was knocked out and the right wing was on fire. Following protocol, Rohrbacher pulled out of formation so his wing plane could take over the lead. Away from the protection of the other bombers, the German fighter planes came after him like a pack of wolves preying on the wounded of the herd. A German fighter coming straight at him took out one of the two remaining engines and the decision was made to bail out.

Unwelcome landing

Surprisingly, every man made it out. They were at 27,000 feet (about five miles up). “At that height there’s not enough oxygen,” explains Rohrbacher, “so I delayed pulling my rip cord until about 5,000 feet.” As he approached the ground he was headed for some trees and wires. Rohrbacher yanked in on part of his chute to steer away from them but the chute didn’t fill back up full in time. “I hit the ground hard — like jumping off a two-story building,” he says.

The landing broke his right ankle and knocked him out. When he came to, he was surrounded by German civilians pelting him with rocks, and the local farmer, whose field he had landed in, was heading for him with a pitch fork. “The planes were still dropping bombs overhead and these people were, rightfully, pretty upset at me,” he says. Ironically, he was rescued in the nick of time by German Gestapo soldiers who herded him off to a car. Because of his ankle, Rohrbacher was forced to crawl to the car, all the while getting kicked, hit with rocks and spit on. By the time he reached the car he was bruised all over.

They took him to a small town and got out of the car and headed toward a large tree in the town square. A crowd was beginning to gather. The 22-year-old Rohrbacher thought that this was it — they were going to hang him then and there on that tree. But after a delay they got back in the car and drove on to another town to an overgrown boy scout camp with Hitler Youth all around. There he met up with his bombardier with a seriously shattered ankle and his navigator who had been beaten beyond recognition.

They took him to a small town and got out of the car and headed toward a large tree in the town square. A crowd was beginning to gather. The 22-year-old Rohrbacher thought that this was it — they were going to hang him then and there on that tree. But after a delay they got back in the car and drove on to another town to an overgrown boy scout camp with Hitler Youth all around. There he met up with his bombardier with a seriously shattered ankle and his navigator who had been beaten beyond recognition.

Interrogation

It was August 6 when Rohrbacher was shot down, a month after the D-Day invasion. In his initial interrogation they were interested in what Rohrbacher knew about how far the Allied lines had progressed. The German interrogator pointed on the map where he thought the Allies were. Rohrbacher, who understood some German, kept telling him to move his finger farther inland. “Before I was done I had them convinced that the Allies had made it all the way to Paris,” Rohrbacher says. This, of course, was far from the actual truth.

Later he was taken to an old prison in Berlin and put into solitary confinement in a room about six by eight feet. “They had a little flap in the door where they checked up on you and fed you bread and “sawdust” coffee for breakfast and a bean gruel soup for lunch and dinner. Rohrbacher was worried when he counted up the markings on the wall from the last guy, they added up to 45 days. But after a few days he was sent by train to Oberursel, the main interrogation center for Allied airmen, where he was again put into solitary.

He was pulled out for interrogation once or twice a day. Noting his German name, the interrogator told him, “You’re on the wrong side, Rohrbacher.” It was a young interrogator who could speak English well, Rohrbacher says. “At first I got away with just name, rank and serial number, but after a few days they started telling me things they knew about me that even I didn’t remember.” He says they knew things like when he went into the service, when he completed various flight schools, when he graduated from high school, and names of his family members. Rohrbacher explains that they had spies who would get this information from hometown newspaper clippings and send the information to Germany. Rohrbacher says he had little information to offer them, anyway, except radio call signs which were changed on a regular basis and worthless to them.

Life in Stalag 3

After four days of interrogation, Lt. Rohrbacher was moved to a collecting camp. As he was walking into the camp someone yelled: “Ho, Ho, Ho, it’s Rohrbacher!” It was Harry Scully, Rohrbacher’s good friend from pilot training. He had been shot down the day before. “It was nice to see someone you knew,” Rohrbacher says.

They were moved to Stalag 3, a permanent POW camp, southeast of Berlin, for Allied Air Force officers. Stalag 3 was where the Great Escape had taken place (depicted in the movie of the same name). This happened only a few months prior to Rohrbacher’s arrival. Only three of the eighty men who attempted the escape through multiple tunnels had made it to freedom. Most were recaptured and fifty of those were executed. The guards clamped down after that and middle of the night bed checks were the norm, says Rohrbacher. “They even had one on Christmas day,” he says.

The barracks had about ten men each, with triple bunks up against the wall and a table and chairs. There was a pot belly stove for heat and cooking. Fuel was short though. “You’d get two coal briquets a day so you would let the room go cold at night. Our room was the meeting room, we always had about twenty guys that would hang out. We had a wind up record player and the spring had broke. One guy in our room from Oregon was a wizard at putting stuff together and improvising. He rigged a weighted powdered milk container with rope and wooden spools stretched around the perimeter of the room that would run that player. It wasn’t exactly perfect but it was music,” he says.

Food was always scarce. Even the German people were suffering so the POWs relied heavily on the intermittent deliveries of Red Cross boxes. “We’d get a tin of Spam from them and we’d split it ten ways — you didn’t get more than a thin slice. We got one loaf of bread a day for the ten of us. We would cut it so thin you could see through it! The crumbs we saved and put in a can. When we had enough we would add some margarine and powdered chocolate and make a cake out of it. One Christmas we got plum pudding from a British care package. We got about one spoonful each of it. We would take margarine, powdered milk and chocolate and mix it up with snow and that was ice cream. If you ate it today you’d probably throw up, but it tasted pretty good then,” he says.

There were always packs of cigarettes included in the packages, Rohrbacher says. “We could’ve done without them because you can’t eat cigarettes. But everybody smoked so we made good use of them. Guys who never smoked in their life started smoking there.” The cigarettes were also great for trading with the guards who would sneak stuff to the POWs under their coats.

Books, bats, balls and even ice skates also came with the Red Cross boxes Rohrbacher says there were two barbed wire fences surrounding the compound with razor wire in between them. A few yards inside of these was another low fence that was off limits to POWs. “Once we were playing a ball game and the ball got hit over this small fence so I jumped over it without thinking, bent down to pick up the ball and a bullet hit the dirt near my hand,” he says. The guard in the tower gave Rohrbacher a threatening look. “I got out of there in a hurry,” he says.

Midnight Evacuation

By January of 1945, the Battle of the Bulge was taking place to the west of the camp and the Russians were closing in on the east. Hitler did not want the prisoners liberated. “In the middle of the night they came around and told us we had fifteen minutes to get ready to leave. Of course we knew we were going to be moved sooner or later, or else they were going to shoot us, one or the other,” Rohrbacher says. So he and the other 11,000 POWs were put on a forced march in the middle of a blizzard with temperatures that dropped as low as twenty below zero.

“We walked all night and the next day and they finally sat us down in this little town. We were paired up in barns to sleep. Scully and I stuck together,” he says. After a rest, they marched another fifteen plus miles to Spremburg where they were herded into boxcars and sent to Nuremberg.

Rohrbacher spent about four days in the cattle cars. “The cars were meant to hold forty people or eight cattle — they had eighty of us packed in a car. It was so tight you couldn’t lay down or sit down. You slept standing up, if you could sleep, and it was cold, I mean cold. We were strafed a few times by aircraft. Luckily our car didn’t get hit. They were steam trains. Whenever they stopped they allowed one guy to go to the back and get hot water from the steam and bring it back to us. It was rusty but it warmed you,” he says.

“I had two pairs of long johns, a winter shirt, pants, an Air Force overcoat, scarf and knitted hat. I made a pair of gloves out of shirt sleeves. About every two or three days I would switch the long johns from the outside with the inside pair.After a couple of weeks like that, you really stink, especially when you were on the train. In the train, you went in your pants because there was no where else to go. You can imagine (the smell) with 80 guys pooping in their pants. I never smelled anything like that in my life. You were permanently sick to your stomach from smelling it. These are the things they don’t show in the movies, but they are the things that stick in your memory,” he says.

Four days of Freedom

They settled into Stalag 8 in Nuremberg and were put in barracks of 50 to 60 men. Food and fuel were scarce. “We had a little pot belly stove (but little fuel) so we ripped boards off the latrine till only the framing remained. The Germans were so mad. They tried to catch us. They had a guy watch but the minute he left we’d get more. The English were bombing us at night, the Americans by day. They were hitting pretty close, it was a scary time,” he says. The Germans had just developed jets and they would fly over the camp. “The first time we heard it go over we all hit the deck. We thought it was a bomb,” he says.

After a couple months they were put on the march again to Mooseburg. At one point they were getting strafed by American planes. Some guys were killed or injured. “They didn’t know who we were, they figured we were German troops,” he says. “I happened to have a roll of toilet paper, I can’t remember where I picked it up but I was guarding it with my life because not many people had toilet paper. So I ran out into a field and in big letters wrote P O W. So they quit shooting at us, then I ran out and got my toilet paper again. Thank God the ground wasn’t wet!”

There were about 10,000 prisoners on the march, spread out over ten to fifteen miles, separated into groups of 100 or 200 men with one or two guards per group, Rohrbacher explains. “So Scully and I decided we were going to try and escape. We went over and sat in the ditch. A German guard came over and asked in German, why we were sitting there, I said “fuy ist krank” which means my “foot is sick.” He scratched his head and said, “Well, okay.” All of a sudden we were all by ourselves, so Scully and I went off into the field. We were on the loose for four days. We were sleeping by day and moving at night. We had no idea where we were going because we had no compass. We ran into so many different things you wouldn’t believe. Call it dumb luck but we never got stopped by anybody, or shot, like a lot of the POWs who tried the same thing,” he says.

“We would take turns checking out places to sleep and one time it was Scully’s turn to check out this barn. It was four or five in the morning, just about daylight. So I’m sitting in this ditch alongside the road smoking a cigarette waiting for him to give me the okay sign and here comes this guy and a girl walking down the road. The guy sees the glow of my cigarette and he asks me for a light, so I held up my cigarette and lit his. He didn’t know what I was doing in the ditch. He probably didn’t care, he was more interested in the girl he had with him,” says Rohrbacher.

“I’m wondering what the heck happened to Scully because it shouldn’t have taken this long so I go to the barn and peek through the door and there is Scully eating and drinking with a half dozen (drunken) German fighter pilots! Scully sees me and says ‘Come on in’ and they hand me a bottle of beer and a bologna sandwich. I hadn’t had a bologna sandwich in a long time. Their planes are sitting in the field because they had no gasoline to fly them. When they found out Scully and I were both pilots, well this made us all buddies. We were sitting there enjoying ourselves and of course I could speak a little German — you could understand some of it anyway. After a while we figured that when they sobered up and realized we were the enemy they might turn us in so we got out of there,” he says.

“We tried to stay out of towns as much as we could and just kept wandering around. We didn’t have anything in mind because we didn’t know where we were and even if we did we wouldn’t know where to go. We came to a bridge and there was a guard house at one end and a German soldier came out and asked us who we were. We just told him we were POWs. The guy took his hat off and scratched his head. He didn’t know what to make of us — why we were out by ourselves and not in a compound or something. He didn’t know what to do with us. It was something he didn’t expect, so he just told us to go ahead.”

Rohrbacher says he and Scully ultimately just found their way back to their fellow POWs still marching. “We were nervous and we weren’t really doing ourselves any good. We were safer with the whole gang,” he says.

Liberation

Rohrbacher and the other prisoners finally arrived at Mooseburg, Stalag 7, outside of Munich, along with about 100,000 other POWs. “The front lines were getting smaller and smaller and the Germans were trying to keep us from getting liberated so they had something to bargain with. The order had gone out from Hitler to not allow any of the prisoners to be freed. In other words we were supposed to get machine gunned before the end of the war, rather than be freed. We were more or less prepared for something like that. Over time we had collected clubs and things. If you stage a rush with enough guys you can overcome them. A lot of guys would get killed or injured but eventually we could’ve taken over a few of their guns and we could have done some good on our side. So we were prepared for that, but we naturally hoped it wouldn’t happen,” he says.

They lived in tents in Stalag 7. “There must have been 100 guys to a tent. When we laid down to sleep we were head-to -toe, side-by-side from one end of the tent to the other, with just a little aisle up the middle. Thank goodness by that time it was beginning to get warmer and we weren’t freezing like we were. It was tough because we weren’t getting anything to eat from the Germans. All we had to eat was what we had ourselves. Of course you’re like a pack rat when you are a POW. Everything that comes your way goes into your pocket for future use, so just about every body had a can or a packet of something in their pocket, so we managed,” Rohrbacher says.

“The war began to get hot where we were. The Germans were on one side of us and the Americans on the other and they are shooting artillery at each other. It was the Fourteenth Armored Division of the General Patton’s Third Army that was coming in. We were in slit trenches. You can actually see the shells going over sitting in the middle like that,” he says.

It was only four hours from the time they began their shooting to the time they put up the flag over Mooseburg, Rohrbacher says. After that Patton came in and gave the POWs a pep talk. Rohrbacher says he was struck by how he really looked like a general. “If you are going to go to war, he’s the kind of guy you want in the front,” he says.

So in April of 1945, after almost ten months of captivity, Rohrbacher was free. The Third Army came in and set up a field kitchen but there were too many POWs to feed. “They finally brought in reinforcements and they started making white bread. We hadn’t had white bread since we’d been shot down. It was just like eating cake. That was a real treat, I’ll never forget that,” he says. It was three or four days before he was moved to a German air base to await a flight to France. “While we were there waiting we’d go out and watch the guys getting on the planes to leave ahead of us. The Germans were flying in with their planes surrendering and coming out with their hands in the air. The MPs would hustle out and take them in. When one German fighter plane came in, the pilot came out and opened up a storage bin behind the cockpit and his girlfriend came out!”

Rohrbacher was finally flown out to Camp Lucky Stripe in France and had his first real meal in a long time. “Right off the bat we got Chicken a la King. They fed us everything they shouldn’t have because we weren’t used to eating rich food. Everybody was going to the toilet every five minutes. There were lines for half a block waiting to get into the latrine,” he says

Going Home

Rohrbacher finally got put on a Liberty ship to head home. He says they couldn’t wait to get back to New York. They were an hour and a half from NYC when, to the dismay of all aboard, the ship was unexpectedly diverted to Trinidad to deliver cargo. It was a week or more before he would arrive home.

After recuperation leave, Rohrbacher was in Atlantic City awaiting reassignment and that’s where he met his wife, Mary, who was vacationing there. He asked her to dance out on the pier and they were married the next month. “That was true of a lot of war romances, you met and got married,” says Mary Rohrbacher. “When you met someone you didn’t even ask where they came from. There is something about having a world war like that — eat, drink and be merry for tomorrow we die. That really was everyone’s attitude. And a lot of them stayed married,” she says. WWII ended just days before they were married.

Note: Bill and Mary Rohrbacher were married almost 65 years and lived in Spencerport. Retired Air Force Major Bill Rohrbacher died in July 2010. Much of the content of this story was excerpted from a video interview with Bill conducted by Chip Compertore, and from interviews with Mary Rohrbacher of Spencerport.

Earlier this year, the Rohrbacher family donated Mr. Rohrbacher’s POW flag to the Spencerport Post Office where it now is flown.